Hockey in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan is a big deal.

As a kid, we wore out the pavement in my neighbourhood playing street hockey. My cousins, friends, and I would lose track of time and forget to eat. But we all had our own buzzer and mine was the sound of my mother yelling at the top of her lungs. In Greek, of course.

I grew up in an immigrant family and my first language was Greek, making my kindergarten year very interesting. My teacher went as far as telling my mom, “Peter is going to need to really improve his English in order to advance to the next grade.”

Aside from improving my English, much of my early life surrounded the WHL’s Moose Jaw Warriors. My father and cousins would take me to “The Crushed Can” Civic Centre for what was the biggest show in town. The superstar at the time was Theoren Fleury, who apart from being my favourite player, made a tangible difference in my life.

Theo happened to be dating a woman that was in charge of the Smith Park outdoor rink, located just a couple of blocks from my house, and would be at the rink hanging out with her. He would give me pointers and help out with my skating and technique. At the time, none of my family had ever played hockey in “the system.” But I thought, “Why not me?”

Despite how foreign ice hockey was to my family, my mother saw the passion I had for the game. She went to the mall and enrolled me in the minor league program. She made her way to the nearest Canadian Tire and purchased every piece of equipment required (at the best discounted prices possible).

Like many Greek immigrants at that time, my parents worked late nights at the restaurant, trying to make ends meet. Even still, they’d wake up for 5:30 a.m. practices and tournaments.

When I was 17 years old, my family decided to move back to Greece. My father stayed back to run the restaurant in Moose Jaw and we would travel back and forth to visit each other.

Not knowing at all if anyone knew what hockey was in southern Europe, I told my mom, “I don’t care if I can’t play hockey ever again. I want to keep my equipment. Please put it in the shipping container.”

As was mandatory for kids my age, I served in the Greek military for six months (a shortened term since I was born in Canada). I went on to study Marketing Management and became a brand manager, representing Spiderman, Iron Man, the Hulk, Garfield, Snoopy, and many more high-profile assets. I was invited to the Iron Man movie set in Los Angeles and had the pleasure of meeting Robert Downey Jr., and Gwyneth Paltrow.

It was a dream job.

But then I re-discovered a dream that I hadn’t thought of in years. In fact, it took me three years to realize that hockey existed in Greece. No one promoted it. No one even talked about it.

One night a friend of mine said, “Let’s go skating.”

“Roller skating?” I replied.

“No, ice skating.”

My heart skipped a beat and the next thing I remember, I was skating on a rink in a suburb of Athens. It felt great to get back on the ice. I skated for two hours straight, speeding by people, around them, between them. I was a kid in a candy shop.

The owner of the rink approached me and said, “Where are you from?”

“Canada,” I said, proudly.

“Here is Jimmy’s email. He will fill you in on the Hellenic Ice Hockey Federation.”

Nine teams throughout Greece. An entire league. When I read Jimmy’s emails, shivers ran down my spine. Hockey … here?

Frankly, that would have been enough for me.

“And you should try out for the Greek National Ice Hockey Team.”

Pardon?

Soccer and basketball are the beating heart of Greek sport. There is a category just beyond that, such as volleyball and water polo, but hockey is not in any category. It isn’t in the sporting stratosphere of Greece.

This made it difficult to get politicians behind it. Finding funding to acquire a proper ice rink with all the IIHF requirements was next to impossible.

So, while playing for Greece, we trained in pop-up arenas in and around Athens. Getting on the ice at a decent time was difficult as the rink owners needed to maximize their revenue and that meant more time for "public skating.” Sometimes we wouldn’t get on the ice until 11 p.m., off at 1 a.m., then work hours later.

There have been some funky makeshift rinks in Greece. They once put ice in a mini amusement park called “Copa Copana” where a children’s pirate ship was in the middle of the ice surface. We trained and played hockey around it.

We traveled to the Czech Republic and even Bulgaria, just to train in a proper facility that wasn’t an amusement park.

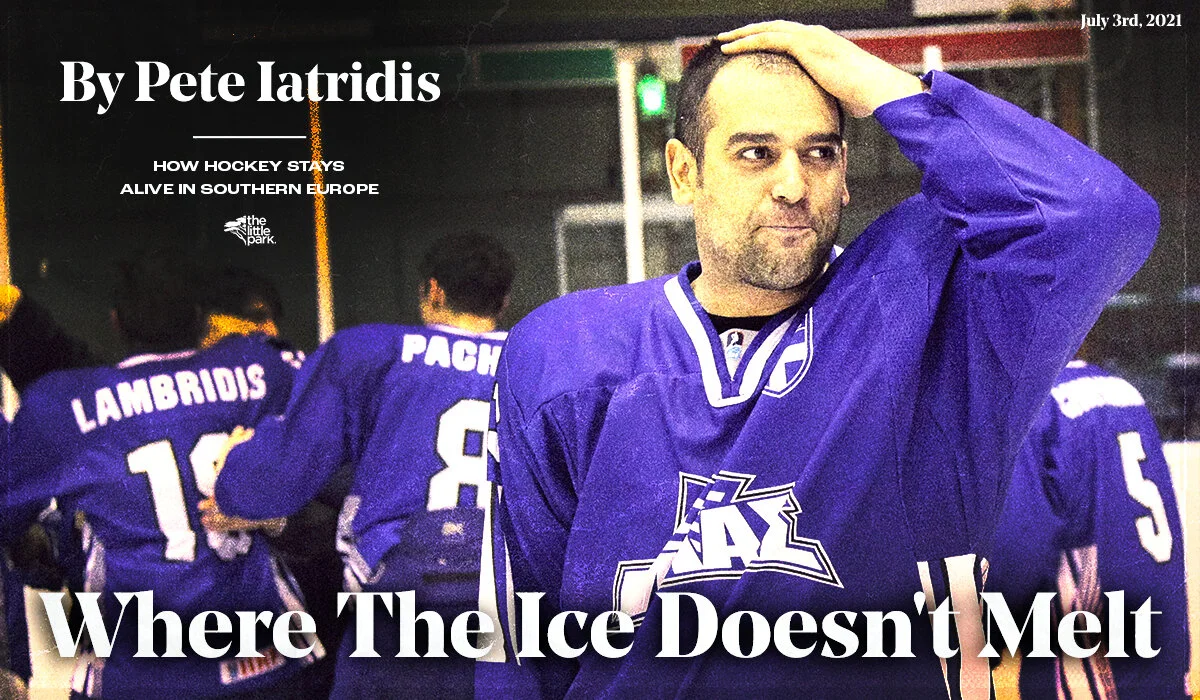

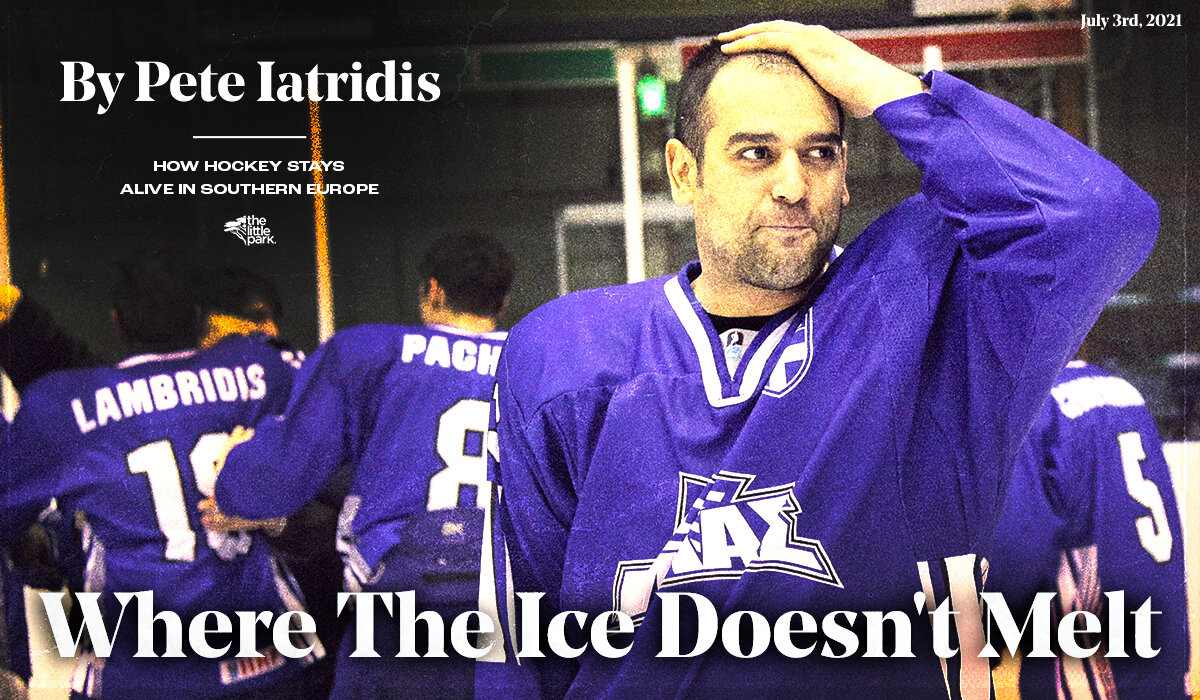

Our team was a mosh posh of different people.

A manager at Microsoft. An ostrich Farmer. An exotic fruit exporter. A restaurant owner, car dealership salesman, bartender, government employee, banker, professional yacht detailer, accountant, tour guide, lawyer, construction worker, and a couple of students studying at the university.

This was my new hockey family, moving together in unison with a common love for the game.

Against all odds, we competed at the IIHF Division III Championships.

At these tournaments, you cross paths with hockey countries even further off the beaten track than Greece, including Mongolia and North Korea. I remember hearing that the North Koreans had all of their televisions taken out of their hotel rooms. They hung out in the hallways and traded us bottles of alcohol for better equipment.

There were reported cases of some Mongolians and North Koreans leaving and blending into the tournament city, leaving their passports behind so they can stay there and start a new life. They didn’t want to go back home. We never did find out what happened to some of those guys.

In 2010, we won silver at the 2010 IIHF Division III World Hockey Championships in Luxembourg. After the win, we danced the popular Greek “Sirtaki” on centre ice. It was the greatest single moment in Greek ice hockey history.

Year after year, hockey brought us together. Each country we played, a unique cultural lesson. I saw and traveled to the corners of the world, living out of my suitcase.

I didn’t think it would end.

After the 2013 World Championships, the IIHF banned Greece from further competing in the future, citing inaccessibility to a proper facility.

We tried everything we possibly could to get a proper, official sized rink built in Greece. We went to the mayor's office and had meetings with the General Secretary of Sports in Greece. We explored fundraising it ourselves and made a pact that if we win the lottery we would open up a rink in Greece to save the sport.

But we never did win the lottery.

Shortly before the ban, I decided to go back to Canada because my father was ill. At the time, the best thing for him and our family was to send him back to Greece to be with my mom and sisters. I saw this as an opportunity to relieve him from handling our shares in the restaurants and enjoy the rest of his life in Greece.

When I took my father back, I met up with our former captain, Jimmy, and over many beers discussed the future. It was kind of funny as we both had plans to return to Canada — Jimmy to Montreal and myself to Moose Jaw.

“You know what?” I told him. “I’d love to get a job with the Warriors, my favourite team growing up.”

I sent in my resume and for nine years served as the Manager of Sales and Marketing for the franchise. That is the beautiful thing about hockey. It comes and goes, but you can find the game again if you love it enough.

That is why the fight to save hockey in Greece hasn’t died. We planted the seed and it will grow when nurtured again.

Anyone that has played in Greece knows the ice hasn’t completely melted.