My 2020 couldn’t have started any better.

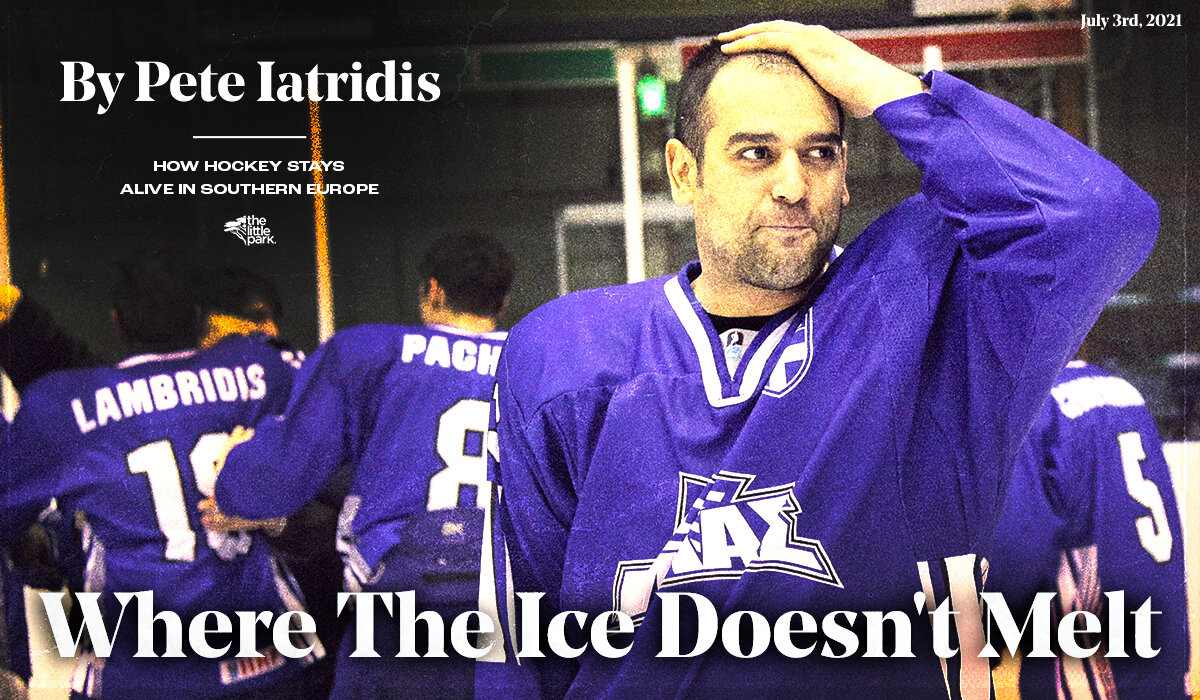

I was invited by the Ottawa Senators to celebrate winning the 2019 NHL Willie O’Ree Community Hero Award during one of their games. To win the award for my work with the Flint Inner City Youth Hockey Program in Michigan was very exciting. I was on a whirlwind hockey world tour.

Here I was, some nine hours away from my home, in a country that lives and breathes hockey, and they were celebrating me.

But as I entered the airport to head home, there was an unease in the atmosphere.

I noticed people wearing face masks and nervously eyeballing one another to determine if they were healthy. I had watched the news about the “coronavirus,” but had the feeling that it was isolated. I had nothing to fear, right?

An uneasiness was taking shape as I flew in Canadian skies.

Not too long after my trip, news reports started to get more intense. Now, it was a pandemic. And while there was still no formal restrictions in place, you could tell that something was about to occur. How would it affect me and our youth hockey program?

The Flint Inner City Youth Hockey Program introduces and teaches the game of hockey to children that live in the city. Many are under-indexed, have never witnessed hockey and certainly have never tried it.

On the tail end of the nine-week program, kids are offered their only chance to play an intra-squad game. It’s an exciting time not only for the kids and their parents, but also the hockey community at large as over 300 people attend the “Big Game.”

And then came the bad news. We were informed by Michigan’s governor that there wouldn’t be any gatherings until further notice due to the COVID-19 outbreak. The immense disappointment knowing that the kids couldn’t play in their one and only game was devastating for everyone involved.

It would become one of several disappointments that the sport would face over the next several months.

During the first stages of the pandemic, there were no ice rinks operating, which meant there were no kids hanging out with their teammates and friends. No parents in the stands cheering on their child and the team. No coaches working on strategies or drills. The referees put away their whistles and there were no fans.

What do we do now?

Virtual calling became the norm, and while it was awkward at first, it gave me a way to stay connected to the hockey community. Our homes and computers became our only vehicle to the outside world.

As we were getting used to this new normal, an incident happened in the U.S. that shook most of the world. While all eyes were on the pandemic, the images of George Floyd’s murder took over and the impact of that moment was palpable.

There was a call to action by citizens across all of North America; enough was enough.

For me, it was recognizing that my voice was being heard across the hockey landscape. People cared what I had to say.

I wanted to think big.

I had made acquaintances with the commissioner of the Ontario Hockey League months prior and we seemed to have an instant connection. I decided to contact him again to ask if there was some way that I could help the OHL with diversity. It was ironic that there was already discussion within the league on finding a person to fill a role that addressed this topic.

The conversations turned into an opportunity of a lifetime and I was offered a newly created position: Director of Cultural Diversity and Inclusion for the Ontario Hockey League. I could not have been more excited and anxious.

This was uncharted waters for both me and the league.

Once I became involved, I was able to connect with players, coaches, general managers, and owners to discuss some critical topics. I also began having conversations and meetings with hockey people from minor to professional hockey across North America.

It was during these discussions that I was able to see the impact of the pandemic on hockey.

Here in the United States, the rebellion and political strife towards stay-at-home orders and mask requirements escalated. Social media began to reveal the outrage that hockey parents were experiencing. There were complaints about their kids not being allowed to skate and notions that the pandemic would end hockey as we know it because rinks would be shuttered.

From my perspective, it was apparent that some folks in hockey looked at the sport as a right to play and not the privilege that it is.

In Canada, it seemed to be a nightmare for many. The national pastime was suddenly on complete pause. Not even the elite level players were allowed to train and minor hockey players were now displaced. One contrast I noted was the overwhelming attitude that there was limited partisanship with the way the country was handling the crisis. There was a sense of, “We are sacrificing for the better good of one another.”

But when it came to hockey, not even that message could lighten the mood.

As virtual calls were set up to carry out my business with the OHL, I could sense that the players were hoping I was bringing good news from the league on a return to play. The hard work and pure ambition of young, elite players was being restrained by an unknown adversary. Coaches and general managers did their gut-level best to be encouraging and to stay connected. For some kids, their chances of proving they are worthy of a professional contract was fading. In major junior hockey, once you are 19 years old, you have one last season of displaying your talent in the league with the hopes of securing a professional contract. This is extremely important. Players that are 18 years old are also in a tough spot in their draft eligible season.

The stakes are high for these young elite athletes. Due to the pandemic, some of their hopes faded away.

Slowly, there began to be a light at the end of the tunnel.

Minor hockey began to wake up in the U.S. at the start of this year with players allowed to begin practicing in small groups — socially distanced and wearing masks. It seemed so odd at first.

Through a bunch of political maneuvering, the rules were relaxed in Michigan to allow for competitive hockey again.

When high school teams reconvened for a shortened season, I took risks that even made me nervous.

I have been an on-ice official since 1986 and was about to start my 34th season, this time wearing a mask. It was incredibly confining and difficult at first. I truly questioned myself as to whether it was worth it. Games were frequently cancelled due to an outbreak amongst a team or school. It was certainly the most interesting season of my career.

My colleagues and players north of the border were not as fortunate. The Ontario Hockey League had to effectively cancel the season and there were no minor hockey games played in Ontario. Many want to put blame on the league or the government, but honestly there is only one to blame: COVID-19.

Now that vaccines are rolled out in the U.S., hockey is poised to make a full return starting this summer with camps.

Canada has a separate set of circumstances, mainly due to the availability of the vaccine. There is a plan to have a limited return to play for minor hockey with an expansion once next season rolls around. The Ontario Hockey League has a renewed vigour as the hopes are to have a full season starting in the fall.

This entire experience has taught many how to cope with disappointment and to remain resilient. I saw kids and coaches implement creative ways to stay interested and involved in the sport. It gave all of us a moment to pause from the grind of the season and address some of the most important topics that we face in our daily lives.

Next season is projected to go on as scheduled and I hope the lessons of the pandemic last a lifetime.

Hockey truly is a privilege.