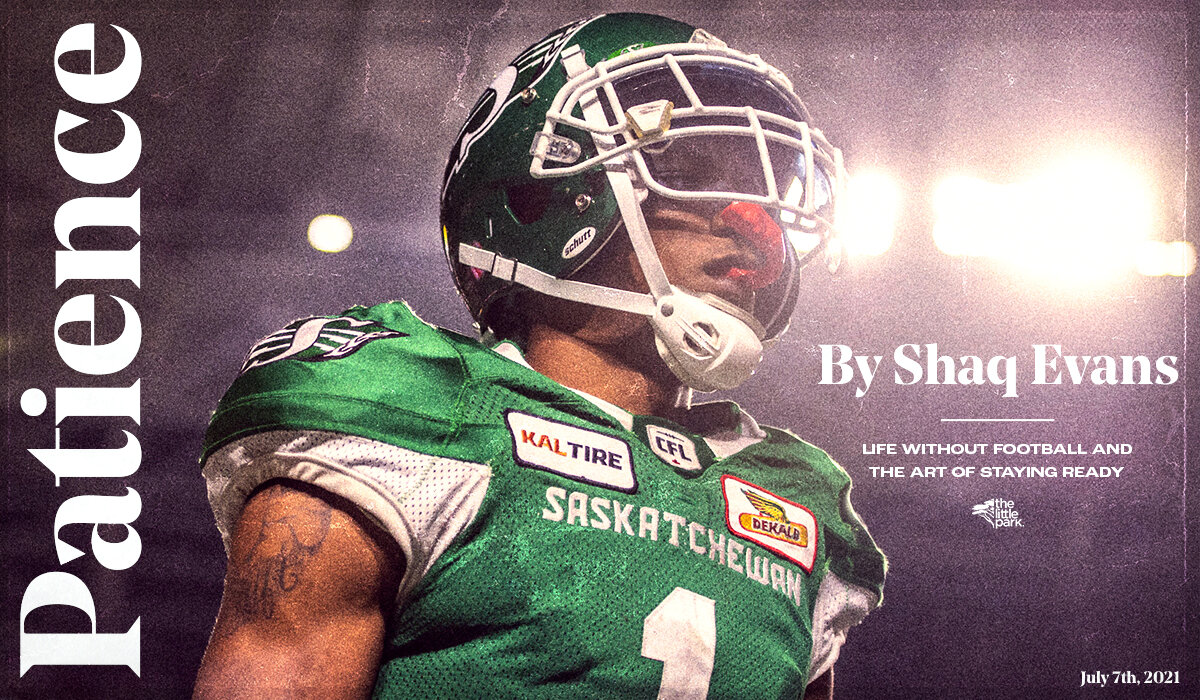

Patience.

It’s a skill I’ve had to practice over my life and especially over the last several months.

When the 2020 CFL season was cancelled on August 17, it meant I was a free agent and every day that followed was a mental battle.

From September to February, I wasn’t really working out. I didn’t know what to do. Depression creeped in and I started to make scenarios up in my head. Even before the season was lost, we didn’t know for sure what was and what wasn’t. I’m an anxious guy and when things are uncertain, it’s tough.

I started thinking, “I might never play football again.”

This pandemic was new territory for me and wasn’t the first time I’ve had to fight to hold onto football.

Eric Yarber is known for coaching some incredible receivers, from Chad Johnson with the Oregon State Beavers to Terrell Owens with the San Francisco 49ers. Today, he works with Robert Woods and Cooper Kupp as the receivers coach for the Los Angeles Rams.

When a guy with Eric’s experience and pedigree tells you that you are a good football player, it goes a long way.

It was words of encouragement like that which made me believe I was destined to go to the NFL out of college.

But after being drafted in 2014 by the New York Jets, my first minicamp was the beginning of a series of downfalls and unfortunate events.

Before minicamp got underway, UCLA had a rule that you had to finish your classes and couldn’t leave early in order to graduate. This meant I wasn’t with the team and couldn’t go to OTAs. I was given an NFL playbook that I hadn’t seen before and that was it.

By the time I did arrive at Jets minicamp, I didn’t have much confidence or chemistry with anyone on the team. No one knew me.

Fourth day of camp, I’m on kickoff, which had never happened before in my career. I hadn’t even played special teams in high school! But I knew I needed to get noticed any way possible.

I’m running down the field and thinking, “OK, this is my moment. I’m going to let everyone know that I’ve arrived.”

I see the fullback and not even worrying about where the ball is. I run full speed and drive my shoulder into him as hard as I can.

A sharp pain. I feel my shoulder rotate a little bit, but I’m hyped up and continue to practice. When all that adrenaline wore off, I knew something was wrong, even despite having a good practice.

An MRI the next day revealed a torn labrum and a need for surgery. Before I could even arrive in the NFL, my year was done.

As I rehabbed that 2014-15 season, the Jets were horrible. At one point, I think we had lost eight in a row and finished the year 4-12.

They fired everyone: coach Rex Ryan, general manager Jon Idzik — who drafted me — and Sanjay Lal, the receivers coach. It seemed like everyone who worked with me was gone. So, as it goes in the NFL, when a new GM comes in, they bring in their guys.

I wasn’t one of “their guys” and so, for the first time in my football career, I was just “a guy.”

The Jets waived me the following September.

I’ll admit it right now, when I first got into the league, I failed a drug test in 2015 and they put me in “the program.” But let me set the record straight, after 2015, I never failed another drug test again and was clean.

When you’re in “the program,” they can pull up on any day to test you between 6 a.m. and 9 p.m.

I remember they showed up one afternoon and I had been drinking water all day. Anyone that knows me knows that I sometimes drink more than a gallon of water a day.

I went in and tested, no problem.

“Your urine is diluted,” they said. “You can’t do this again or it will be a violation.”

Fast forward six months during the off-season, I’m sick in my apartment in downtown L.A., for almost three days. As one does, I’m drinking fluids constantly.

As luck would have it, they call me in for a test.

I go down there and put it in the cup. Diluted, again. I think to myself, “Oh no.”

“Can we do this again so I can get a little more yellow in there?” I asked.

“No. Once it is in the cup, that’s it.”

Two months later, I head to Jacksonville for off-season training. When you’re in “the program” you have to notify the league of your location.

I called the office days in advance and left a message saying I was going to be in Jacksonville, where I signed in 2015 a few weeks after being cut by the Jets. The Jaguars were starting their off-season programs.

I got a call from a tester when I was in Jacksonville getting my gear on for a workout.

“Hello Shaquelle. I’m at your apartment in L.A. You have a test.”

I’m like, “I called three days ago and let everyone know that I’m going to be here today.”

He says, “They told me you’d be at your apartment.”

I call the offices and I’m like, “Why is there a tester at my apartment? I left a message that I’d be here.”

They respond, “You just said ‘Jacksonville Jaguars stadium.’ No specific address was provided.”

Without a formal address, it was like I had never called. I assumed the NFL knew where the Jaguars’ stadium was. If not, they could have Googled it.

Taking all of these instances into account, the NFL had to decide what to do with me.

Late in the 2016-2017 season, after spending two years on and off practice squads in Jacksonville and New England, the Dallas Cowboys brought me in. They had the best record in the league that year and I was feeling good.

I knew I was going to be here for a couple playoff games, but had my sights set on next year. That was going to be my time to come in for a fresh season and ready to rock.

During that off-season, the NFL made their decision to suspend me, which led to the Cowboys subsequently letting me go. Not because of performance, but because of a BS suspension that I should have never got.

That ruined any chance of finding another team and I ended up being out of football that entire year.

—

Although it has never been quite like this pandemic, I’ve had football taken away from me before. I felt cheated by what happened in my NFL career.

On the heels of my drug violation suspension in 2017, I went through a mental struggle. A part of me felt like my career was done back then and that feeling crept back in during this pandemic.

In both cases, the other part of me knew I still needed to play football.

It’s a mental struggle to stay ready for a call that might never come. But when it does, you don’t want to be caught unprepared. So you keep grinding.

In 2017, Jeremy O’Day and the Saskatchewan Roughriders brought me in for a workout. I stayed ready and impressed them. Since then, the CFL has rewarded me with a career.

When I got the call that we were going to play CFL football in 2021, I was ecstatic.

I know a lot of Canadian fans have felt sadness and even anger at all this uncertainty and lost time. I know how much football means to everyone across Canada and especially in Saskatchewan. Trust me, I know.

That patience, man, it’s something you have to keep practising.

It’s time to get back doing what we love again. I’m going to enjoy every moment because you can’t take this game for granted.